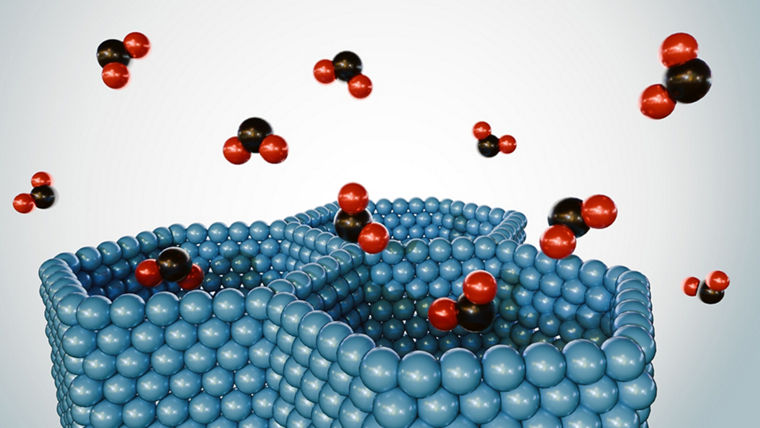

MOF stands for “metal–organic frameworks.” These are tiny structures in which metal ions are connected to organic material. The metallic components form the corner points; the organic molecular chains create the links between them. Together they produce a porous architecture that can serve completely different functions depending on the building blocks used.

What MOFs have in common is that their structure allows them to take up and release large amounts of substances within a small volume. They can also drive chemical reactions and even generate electricity. Heiner Linke, chair of the Nobel Committee for Chemistry, praised the advance: “Metal–organic frameworks hold enormous potential and offer previously unforeseen opportunities for tailor-made materials with new functions.”

The first steps

The first steps toward their development were taken by Richard Robson, born in 1937 in the United Kingdom and now a professor at the University of Melbourne in Australia. In 1989, he began combining positively charged copper ions with a four-armed molecule that had a chemical group at each arm attracted to the copper ions. The substances assembled into a well-ordered, open crystal—a solid like a diamond filled with countless cavities. Robson recognized the potential of his discovery, but it was still unstable.

Between 1992 and 2003, Susumu Kitagawa, born in Japan in 1951, and Omar M. Yaghi, born in 1965 in Jordan to Palestinian refugee parents, advanced Robson’s discovery.

Kitagawa, a professor in his hometown of Kyoto, demonstrated that MOFs can capture and release gases. He also predicted they could be made flexible.

Yaghi, now a professor at the University of California, Berkeley, created highly stable MOFs. He showed they can be modified through rational design to endow them with new and desirable properties.

This fundamental research enabled chemists worldwide to produce thousands of different MOFs capable of tackling major challenges facing humanity. The Nobel committee cites, for example, removing so-called “forever chemicals” (PFAS) from water, breaking down trace pharmaceuticals in the environment, capturing carbon dioxide, and even harvesting water from desert air.

In a statement last year, Omar M. Yaghi highlighted the capture of greenhouse gases such as CO2 and methane, as well as producing clean water from air, among key application areas for MOFs.

In a collaboration at UC Berkeley, artificial intelligence is now being used to design MOF structures. Yaghi expects research that once took years to be completed in weeks. He sees the field in a race against the most pressing problems of our time: global warming and water scarcity.

Carbon dioxide from hot exhaust gases

A paper published this year in Science drew particular attention. Researchers at Berkeley developed a MOF that can capture carbon dioxide from hot industrial exhaust streams and be reused repeatedly. The current dominant method removes carbon using liquid amines from power plant or industrial flue gases, but that reaction only works between 40 and 60 degrees Celsius. The new MOF-based approach operates between 200 and 500 degrees Celsius (390 to 932 °F)—exactly the range of many industrial emissions. The CO2 is effectively trapped within the framework and can then be extracted, utilized, or sequestered. The newly developed MOFs remain ready for reuse. This technology could be deployed in cement, steel, and chemical plants.

“It requires costly infrastructure to cool these hot gas streams to the appropriate temperatures for existing carbon-capture technologies to work,” Science quotes Kurtis Carsch, one of the study’s two lead authors and a postdoctoral researcher at UC Berkeley, as saying. “Our discovery will change how scientists think about carbon capture. We found that a MOF can capture carbon dioxide at unprecedented temperatures—temperatures relevant to many CO2-emitting processes. That was something previously thought impossible for a porous material.”

The material consists of a porous, crystalline arrangement of metal ions and organic linkers, with an internal surface area roughly equivalent to six football fields per tablespoon.

Also at the Marl Chemical Park: carbon dioxide as a feedstock.

New approaches to capturing carbon dioxide are also being developed in Germany. On the site of the Marl Chemical Park, part of Evonik, the start-up Greenlyte Carbon Technologies plans to build a plant for the carbon-neutral production of e-methanol from air. The three Greenlyte managing directors—Florian Hildebrand (35), Martin Schmickler (32), and Niklas Friederichsen (37)—have raised more than €45 million in venture capital and public funding. The pilot plant, also in the Ruhr region, is located at the Center for Fuel Cell Technology in Duisburg.

The goal is to produce synthetic fuels from CO2 captured from ambient air and hydrogen generated in the same process—both produced using green energy. Brand name: “Liquid Solar.” The company, a spin-off from RWTH Aachen University and the University of Duisburg-Essen (UDE), has been working on this technology for 17 years. It is based on the work and patents of UDE scientist Peter Behr.

»Decarbonizing aviation and shipping isn’t feasible without scalable e-fuels. With LiquidSolar, Greenlyte supplies the essential green molecules to make that possible. Our project at the Marl Chemical Park shows how we can now industrially scale this critical value chain in Germany.«

Florian Hildebrand CEO and Co-Founder Greenlyte

In the process, air is passed over a non-toxic, water-based liquid. The carbon dioxide (CO2) binds with the liquid to form bicarbonate (HCO3−). No heat, pressure, or toxic substances are required. The bound carbon dioxide can be collected and stored until green electricity—such as surplus power from solar or wind—is available. Then carbon and hydrogen are combined via electrolysis and can be used as the basis for so-called e-fuels. Potential customers include shipping companies or airlines that cannot easily switch to battery-powered systems. The reaction liquid—the absorbent—can then be returned to the cycle.

»Greenlyte’s production facility is a welcome next step for the Marl Chemical Park as it continues to expand its hydrogen hub.«

Thomas Basten Marl Chemical Park site manager

The plant at the Marl Chemical Park is slated to go into operation in 2027 and produce e-methanol. It is designed for thirty times the capacity of the Duisburg pilot facility. With its help, up to 1,400 metric tons (1,540 short tons) of carbon dioxide per year are to be captured from ambient air. In an integrated process, approximately 200 metric tons (220 short tons) of green hydrogen will also be produced. In a subsequent step, the molecules formed in the process—green hydrogen and green carbon dioxide—will be synthesized into up to 1,000 metric tons (1,100 short tons) of green e-methanol per year.

For 2028, a facility is planned at Düsseldorf International Airport to produce 150 metric tons (165 short tons) of aviation fuel per year. By 2030, a large-scale plant is to be built in North Africa or southern Spain, where wind and solar yield even higher outputs.

The Nobel laureates’ MOFs can even operate without large energy inputs. They therefore offer a major opportunity for industries that cannot reduce their CO2 emissions to zero to participate in a climate-neutral economy.

ELEMENTS-Newsletter

Receive exciting insights into Evonik’s research and its societal relevance—conveniently by email.